- Mania Madness II – The Finals - April 1, 2024

- Norm Of The North – 2023 AFC North Preview - September 4, 2023

- Gold For Gold – Denver Nuggets NBA Finals Preview - June 1, 2023

Thank You for coming back for the conclusion of this four part series on why debating the superiority of different NBA eras is a futile exercise. In part one, we highlighted how nostalgia and context alter our memory of past eras. In part two, we looked at how the average NBA player today is better than they were 30 years ago and in part three, we dispelled the myth that modern NBA players lack fundamentals.

It’s been a long, strange journey thus far. Now it’s time to bring it all together.

So before we hurry up to the end, here’s what I want you to think about. If someone asked you “what is the best decade of the NBA?” I bet you have an answer to that question.

If someone asked you “what is the best part of a circle?” Would you be able to answer that? Of course not-a circle is one continuous line with no defined points or sides. It is a singular figure that is ultimately one thing, not disparate entities.

My point here, is that picking the “best” NBA era would be the same as trying to pick the “best” part of a circle. It is a question with no answer.

Confused yet? Don’t worry, I’ll explain.

Part 4: A Snake Eating Its Own Tail

So far we’ve been primarily focused on the most recent NBA decade (2010-2019) versus the 1990s. But to really see the big picture here we have to step further back. I mean way, way back to when games aired on tape delay and the shorts were…upsettingly short.

I’m talking about the 1962 NBA season.

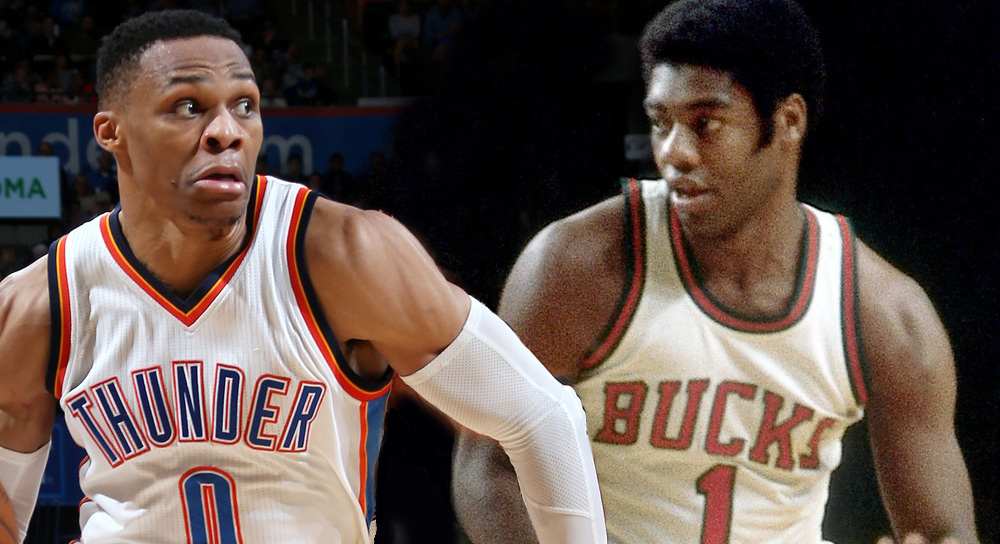

Before we get into that, specifically, let’s look at some of the most iconic statistical achievements in NBA history. I don’t mean those in relatively recent memory, such as Kobe Bryant’s 81 point game against Toronto, the Golden State Warriors’ recent 73-9 regular season or Russell Westbrook’s three straight seasons of triple-doubles.

If we’re talking about the old stuff, to me there are three iconic numbers that come to mind. Wilt Chamberlain’s 100 point game, the season Chamberlain averaged over 50 points per game and Oscar Robertson’s triple-double season.

Here’s the thing most people don’t realize: the year Wilt Chamberlain averaged 50.4 points per game was the 1962 season. The year Oscar Robertson averaged a triple-double…was also the 1962 season.

Additionally, five NBA players averaged over 30 points per game that year. There are actually technically six (Elgin Baylor averaged 38.8 ppg but only played 48 games due to injury). Walt Bellamy, a rookie at the time, averaged 32 points per game.

So what the heck happened in 1962 to cause such an insane scoring boom?

Well, what happened actually happened in 1955, with the introduction of the shot clock. Prior to that innovation, teams would get the lead and just stall for as long as possible, not giving up possession to the other team in order to stay ahead.

This was a league-wide practice but most commonly employed against the Lakers at the time. The game’s first true superstar, George Mikan, was a Laker in the 1950s. If you got a lead against them, the most important thing was to keep the ball out of Mikan’s hands.

This of course, lead to very boring basketball. Attendance and interest in the young NBA was fledgling due to Mikan’s dominance. As a cure to this problem of pace, the shot clock was invented.

It still took seven years for the statistical boom, however. The shot clock immediately led to increased possessions but not necessarily increased scoring. But by 1962, players had fully adapted, learning completely new ways to conceptualize offensive principles. It wasn’t just the stars, either, as league scoring averages were nearly 120 points per game in 1962.

So far that makes sense: but why did it stop?

The answer is simple: offense develops before defense. You can’t plan a defense for an offensive attack you have no prior knowledge of. This isn’t even my idea, this comes straight from the mouth of legendary Celtics’ coach Red Auerbach:

“Basketball is like war in that the offensive weapons are developed first, and it always takes a while for the defense to catch up.”

Defenses did eventually catch up and by 1972 scoring averages dropped to 112 points per game. When asked about it 1972, Jerry West had this to say about it:

“Defenses all around the league are more sophisticated. This has necessitated a change in all players. The days of four or five guys averaging 30 points are gone.”

So what does this have to do with the 1990s versus today?

The NBA is all about cycles. What happened between 1955 and 1972 has happened, over and over again. Offense is what drives ticket sales, after all. And we must never forget that basketball, at the professional level, is entertainment.

When defenses catch on and the games slow down and become boring, rules are tweaked to increase excitement level. Defenses catch up eventually and more tweaks are made. You may not like every single change but basketball, as a concept, is a living thing. Like all living things it must grow and change or it will die.

The next most major innovation was the three point line. It, of course, was brought in to increase excitement. It didn’t come to the NBA until 1979 after the merger with the ABA, which had already been utilizing it.

Remember George Mikan? Well, he happened to be ABA commissioner and he had this to say about the three point line in 1968: (the three pointer) “”would give the smaller player a chance to score and open up the defense to make the game more enjoyable for the fans.”

Mikan would prove to be absolutely correct. He should know, since rules had to be implemented to increase the game’s interest basically because of him. (He’s also the reason they outlawed goaltending).

Although we didn’t see a barrage of three point shooting in the 1980’s, we did see the offensive game open up a bit due to the improved spacing the three point line created. This, in turn, gave us the Showtime Lakers, Bird’s Celtics and opened up driving lanes for a young guard by the name of Michael Jordan.

Of course, the defenses caught up, as they always do. The response to this more open style of play, defensively, was to ugly up the game. The most extreme example is the Bad Boy Pistons of the late 80s and their infamous “Jordan rules.”

And here we come back to our beloved 1990s. With some exceptions (the Run TMC Warriors, the John Stockton-led Utah Jazz offense, the pre-injury Penny Hardaway), the game got mired in the muck of physical defense.

It shouldn’t have been popular. It was a far cry from the beautiful, free flowing basketball Magic Johnson and Larry Bird brought to the NBA 10 years earlier when they fundamentally saved it from the brink of collapse.

But remember back to part one of this series and our discussion of context. The nation, by and large, was in a good place in the 1990s. Our economy was doing well, we were in one of the very brief periods in this nation’s history of not being at war…on a national level, things were pretty good. That contentment filters the way we consume everything, including our sports.

Consequently, this also may explain some of the truly god awful fashion choices we made in the 1990s.

It only worked in the NBA for one reason: Michael Jordan. He was so good, so superhuman, that he transcended what was ultimately a bad brand of basketball and the league thrived anyway. Ever see a movie that isn’t good but one person’s acting performance completely saves the film? It was kind of like that.

When Jordan retired after the 1998 season, the mask came off and we saw what the NBA had really become during the 1990s. There’s a valid reason nobody fondly remembers the league between roughly 1999 and 2003-it just wasn’t very good.

It didn’t help that the league had an image problem at the turn of the century. Its three best players at the time were Shaquille O’Neal, Tim Duncan and Allen Iverson. O’Neal was too dominant to be captivating, Duncan too bland. Iverson was brash and dynamic but was somewhat labeled a “thug” and was a turn off to “basketball traditionalists” (i.e. white people).

*The strange, not so subtly racist response to Iverson’s rise to stardom is a fascinating NBA thought experiment in and of itself. Maybe I’ll tackle that one in the next pandemic…*

The NBA did get one thing right with Iverson, however. His slashing, attacking, devil-may-care brand of offense was something incredible to behold. At the same time, the NBA had always been the land of giants and they were becoming short in supply. With the exception of O’Neal, there just weren’t a bunch of great centers anymore. What Iverson showed was that the game could be just as great if it focused on the little guys.

The hand-check brand of defense was slowly done away with. No longer could a defender use hands, forearms or shoulders to overpower an offensive player. For those who miss that style, I understand. You may prefer a more physical brand of basketball.

Just don’t try to claim it was good defense. I’ve played this game since I was seven and I can be a physical defender when I need to be. But here’s the thing we never like to admit: when you start getting physical defensively, it’s because you aren’t a good enough defender to stop your opponent legitimately.

As with the shot clock, this change took a little while to take hold. When hand-checking was first outlawed in 2004, it wasn’t something that was taken advantage of by the league at large because players had spent their whole lives playing with hand checking.

Some players took advantage quickly, which is why we had a rash of overrated, inefficient perimeter players in the mid-2000s. But the league as a whole wouldn’t find a way to take advantage of it for a few more years, just as it took seven years after the implementation of the shot clock for 1962’s stat boom.

Early harbingers were there. Steve Nash never wins his MVP awards in 2004 and 2005 without the absence of hand checking. That doesn’t make Nash’s MVPs any more or less valid than those others won when hand checking was legal-you play within the parameters of your era.

What we’ve seen in the 2010s is nothing more than the next part of the cycle. Hand checking was outlawed to help a sport that was becoming stagnant. New players grew up with those rules and adapted to them, bringing some of the things we have seen the past ten years.

Oscar Robertson’s triple-double season used to seem impossible, a feat that would never be repeated. But, Roberston had help due to the change of the shot clock rules. When we got similar help by outlawing hand checking, that once “unrepeatable” season was repeated by Russell Westbrook. Three times in a row.

Without those changes, we don’t get James Harden’s unique style of offense. We don’t get LeBron James, fundamentally a small forward (as basketball becomes more positionless), leading the NBA in assists at 35 years old. We don’t get Steph Curry’s absolute onslaught of the league’s three-point records.

What we have seen in this decade is no different than what happened in 1962. It’s not that players don’t play defense, we are just at the part of the cycle where offense is ahead of the defense. I was taught sound defensive principles by good coaches growing up. Nobody ever taught me how to guard a 7 footer like Kevin Durant who can handle the ball like a guard. Nobody ever taught me how to stop a point guard who can hit from six steps behind the three point line consistently.

The defense will eventually catch up…it always does. Nobody knew how to stop Jordan until the Pistons invented the Jordan Rules. Jordan was good enough to find a way to overcome it. Better offense leads to better defense out of necessity, which in turn leads to even better offense, so on and so forth until the end of time.

Defenses may not figure out how to stop Steph Curry during his career but don’t be surprised if Trae Young finds life a little harder than Curry did. James Harden’s step-back may seem unstoppable but based on league history, I’ll bet Luka Doncic is going to have some very frustrating nights in his future.

We’ve already seen it, to a degree. Remember two years ago when Corey Brewer of the Philadelphia 76ers started picking up Harden full-court and it frustrated Harden excessively? Brewer figured out how to contain Harden but it’s such a strange way to play defense we don’t have players ready to implement that strategy all the time.

So if you say you prefer the 90s to today, that’s allowed. You prefer that particular style and style preference is completely subjective. But what you can’t forget is that we have the style we have now as a direct result of the style we had then.

No era of the NBA exists in a vacuum. Each era is both connected to and informed by the eras that preceded it and those that followed it. Basketball in the 90s (and 80s, 70s etc.) is the result of the basketball that came before it. And the way we remember past eras is always influenced by the basketball going on now.

That’s why a basketball being round is so perfect: it is its own metaphor. There is no beginning or end to a basketball, it just is. The game is the same. And like a perfect jump shot, it’s always in rotation.

If you’ve read this whole thing, all I can say is, Thank You. This was much longer than what we typically run here and it’s not the type of stuff we usually do. But this is how I try to think about the game. I view it not as just a sport but a fascinating tale, full of different chapters and characters that is always evolving. I hope by reading this, you’ve found some new ways to view basketball or anything else for that matter.

And if you want to debate any of this with me, feel free.

But you better come correct.