- Mania Madness II – The Finals - April 1, 2024

- Norm Of The North – 2023 AFC North Preview - September 4, 2023

- Gold For Gold – Denver Nuggets NBA Finals Preview - June 1, 2023

Part 2: The Evolution Of The Average

Today we continue to examine why the debates about why one era of the NBA may be better than another is ultimately a pointless process. In part one of this series, we examined the subjective nature of the sports viewing experience as well as the impact time, nostalgia and countless other factors influence how we recall certain events.

To summarize it briefly, your own experience is colored by a thousand little things which may not be the exact same as my thousand little things. Although the end result of what happened on the court is an objective fact, such as the final score, the way in which two separate people perceive that game is an entirely unique experience for each individual.

That does not mean, however, that there aren’t objectively true things that prove the game overall is better today than it was in the 1990s. (Or any other era-this same line of thinking can be extrapolated to any inter-generational debate).

Here’s where this debate gets weird. To the fan who is touting the 90s as some glory days period of the NBA, they act as if the game is somehow something that does not evolve. As if the overall skill of players has followed a mountain climb path that reached its summit in 1996 and has been on the way down ever since.

That argument is of course, outright silly. If you were to somehow chart overall player skill from the dawn of the NBA until now, you wouldn’t see a triangle with a clear peak, you would see a line graph that will continue to exponentially rise upwards.

We accept that this is the case in just about everything except sports, as if sport is the one bastion against the trends of evolution. In my day job, I work in the veterinary field. We are better at veterinary medicine than we were 20 years ago, simply because we know more. Our predecessors did their best, based on what their predecessors had figured out, and then they made some innovations of their own.

We, in turn, have more information to work off of, making us better at our jobs. The veterinary professionals 30 years from now will have even more to build off of and do even greater things.

This isn’t exactly reinventing the wheel and we are all okay with that line of thinking. Unless, heaven forbid, we suggest to an avid NBA fan that basketball is actually better now than it was in a previous era. That line of thinking gets treated by some as heretical, even though in any other aspect of life, we believe the exact opposite to be true.

So now lets get to the actual basketball. Whenever I get into one of these “90s vs today” debates, the typical first line of defense for the 90s apologist is to rattle off the big names. Jordan. Olajuwon. Malone. Ewing. Barkley. Robinson. Stockton. In most cases, this is about the end of their argument.

And yes, of course those are some legendary names. Jordan is to most, the GOAT. In all time power forward rankings, Malone and Barkley are in most people’s top three. Stockton holds assists and steals records that will likely never be broken.

What these people fail to see is that these are outliers. Legendary players all, undoubtedly. But we could take any decade and rattle off the names and it would be almost equally impressive. Now, I will concede the 1990s in particular had one of the better lists of upper echelon talent but it isn’t alone in having greatness at the top.

The 1960s had Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, Oscar Robertson, Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, just to name a few. That is one heck of a list. The 1980s had Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Isaiah Thomas, the old version of Kareem Abdul Jabbar and the young version of Michael Jordan. Also remarkably impressive.

But part of why those names are so impressive is nothing more than the passage of time. Remember the argument yesterday about the iconic image of Michael Jordan’s legacy: over time these figures become almost mythological. Yes, they were great but the passage of time makes them something beyond that.

Is today’s list of upper-tier superstars any less impressive? Try to distance yourself from the images of those great 90s players and try to remember them as the actual basketball players they were. Now compare how great a list that is to this one: LeBron James. Kevin Durant. Steph Curry. James Harden. Kawhi Leonard. Russell Westbrook. Giannis Antetokounmpo.

25 years from now those names will be just as deified as the ones from the 1990s (with the exception of Jordan who hit a cultural importance level that will likely never be reached by any athlete ever again). They just haven’t had time to become legends to us yet.

But the real flaw in arguing about great players from different decades is absurdly simple: greats are great. That’s really all there is to it. If you want to really get the feel for an era, you have to check out the average players.

Take any given NBA roster at almost any point in league history and there are 5-6 guys (if not more) who are, for lack of a better term, kind of irrelevant. That’s not to say they weren’t good basketball players or didn’t do things to help their teams win. They did but there were also about 100 other guys in the league who could do the same thing as them.

Take for example Raja Bell of the mid-2000s Phoenix Suns. Bell played some pretty solid man to man defense, could knock down an open three, ran well in transition. He was a key piece to that Suns team but if they didn’t have him, they could’ve found those same skills easily with another player. Steph Currys and Dirk Nowitzkis don’t grow on trees. Raja Bells do.

This is where you can definitively see the difference between the modern game and that of the 1990s.

If you look at the statistics of star players, you’re going to get star numbers. If you look at league averages, you get a clearer picture of the league as a whole.

Effective field goal percentage is one of those advanced statistics most people like to discount. Basically, it adjusts field goal percentage to account for the fact that a 3 point shot is worth 1.5 times more than a 2 point shot. To break down how that works, here is the simplest explanation I can find.

If a player takes 10 two point field goal attempts and makes four of them, their effective field goal percentage (EFG) is 40%. But, if all those attempts were three pointers and the player still made four of them, their effective field goal percentage is 60%. They technically shot the same shooting percentage but the three point shooter gained more points, making it more effective.

Since the ultimate goal is to score more points than your opponent, this is a more accurate representation of how well you are actually shooting. It also doesn’t matter how many threes were taken versus twos, which addresses the difference in how many three pointers are attempted today versus the 1990s.

When you look at the numbers, it is pretty clear when the better shooters existed. Between 1990 and 1999, the league average EFG% was .487. Between the years 2010 and 2019, the league average EFG% was .504. The highest EFG reached in the 1990s was .500 in the 94-95 season. Between 2010 and 2019, the .500 mark was topped six times. In the now abbreviated 2020 season, we reached the highest league EFG percentage in history at .528.

So what does that mean? It means that shooters, across the board, not just the megastars, are better shooters than they used to be. Statistics are not the be-all-end-all of sports debates but sometimes you just can’t argue the numbers. Shooters are objectively more consistent than they were 25 years ago.

The counter argument to this is usually “well, they shoot a lot more three pointers now.” That argument simply doesn’t hold water, mathematically. Shooting an increased number of shots will not raise an average. If anything it will lower it. I’m about a 70% free throw shooter. Could I hit ten in a row? Sure. That doesn’t mean I’m perfect from the line, its just a small sample size. Have me shoot 100 of them, I’ll come back to my average.

So in the 90s they shot less threes, therefore taking relatively easier shots in terms of distance and were still shooting less effectively than the players in the modern NBA.

I get that some people have a statistic phobia. I understand, I have an English degree. Numbers are not my friend. So what about if we look at the actual language we used to use for role players (the average guys) in the 90s?

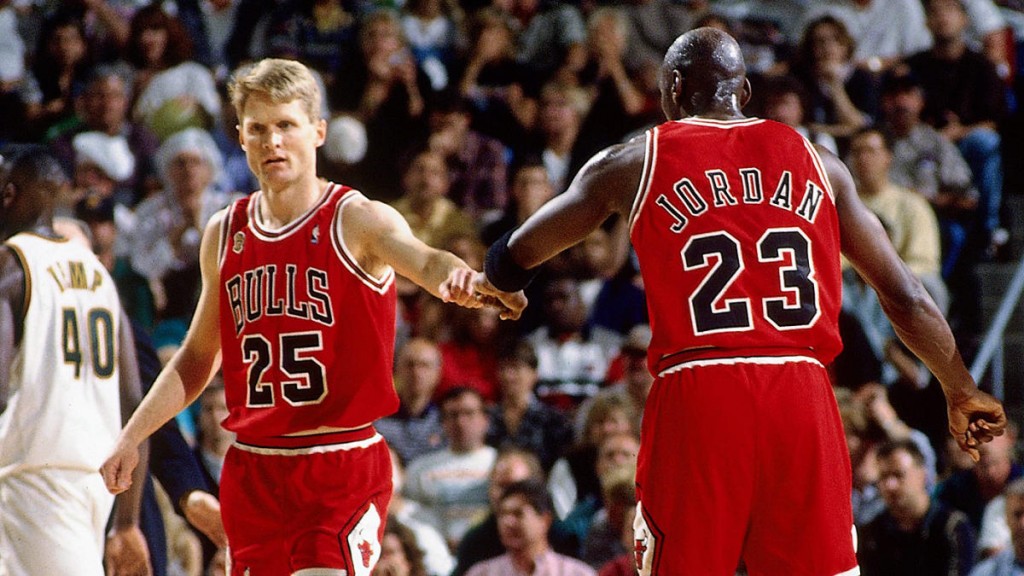

Before Steve Kerr was a multiple time championship winning coach, he was one of the better role players of his day, winning titles with both the Chicago Bulls and the San Antonio Spurs. Specifically, Kerr was touted as a “three point specialist.” Does that phrase feel antiquated to anybody else?

Yes, Kerr was a three point specialist, meaning his only role on the team really was to spot up and knock down open threes when defenses collapsed on a Jordan drive or Tim Duncan post up. And Kerr was damn good at it. He filled a specific role. That role is no longer required in the modern NBA.

There are no more three point specialists because to make it in today’s game, you need to be able to hit threes at a consistent rate, at least for perimeter players. The few that can’t do that have some other outlier skill beyond the average player, such as Ben Simmons, Russell Westbrook or even DeMar DeRozan.

Imagine Kerr walking into an NBA tryout today. “You can shoot threes? Great, so can everyone else here. What else can you do?”

This wasn’t just for shooters either. Up until relatively recently, the league was always good for a few goons. Guys who came in, got rebounds, set screens, threw some elbows, fouled out and called it a day.

There is no roster spot set aside for goons anymore. Their skill sets are too limited for what is asked of the modern player, roster spots too valuable. The last one we really had was Kendrick Perkins, whose lack of meaningful contributions is still considered part of what dragged down the promising 2012 Oklahoma City Thunder.

Now, I realize I’ve mostly talked about shooting, which is far from the only skill needed in basketball. (Though, since the point of the game is to score, it is arguably the most important skill). Let’s look at another apologist argument against the modern game that doesn’t hold up.

“There’s no defense anymore! It’s just a track meet and shooting threes!”

The defense portion will primarily be addressed in part four of this series but a quick word on it here: defense in the 90s was not better than it is today it was just different. Think back on when Jordan used to drive to the hoop: 3-4 guys would converge on him. The advocates of the old school will point to that and tout it as great defense.

It was, but only because the offensive skill of the rest of the team allowed it to happen. If you’re going to collapse on Jordan, make sure Pippen is covered and contest if the ball goes to Kerr or John Paxson. It’s easier to play good defense when there are less legitimate offensive threats on the floor.

Try that same mentality today with say, the Boston Celtics. So you want to take Jayson Tatum away? OK, who are you going to leave open? Because there’s no Steve Kerr out there, you’re going to give an easy look to Jaylen Brown, Gordon Hayward or Kemba Walker.

Defenders weren’t better then are they aren’t better now. They just had the luxury of more help then.

A quick side note here: I’ve seen this argument from the 90s fans that’s becoming more laughable with each passing year: “too many layups! Send him to the line and make him earn the free throws!”

Maybe that worked 30 years ago but it’s quaint today. The league average free throw percentage for the 2010s is 76%. In comparison, the 90s average was 74%. If you run that number back further you will see free throw shooting has steadily improved since the dawn of time (noticing a trend yet?). As free throw shooters become better, not getting a crucial foul is more important than the moral victory of not giving up a layup.

I’ve also always loved the contradictory nature of the phrase. “Earn their free throws.” It’s right there in the name: “free.” As in, “not earned.”

Then there are the complaints that the game is a track meet today. Yes, it is and for me personally, that is infinitely more entertaining than watching Patrick Ewing and Alonzo Mourning slam into each other for two hours while eight other guys stand and watch.

But they use “track meet” as a derogatory term as if it implies a lack of skill from the players. It’s also flat out untrue. NBA teams averaged 95 possessions per 48 minutes in the 2010s, versus 94 possessions per 48 minutes in the 1990s.

If number of possessions are the same, shouldn’t the points per game be the same? Well, in the 2010s, NBA teams averaged 102 points per game. In the 1990s, the average was 101 points per game.

So those who tell you defense was better in the 90s just want something to hold onto about their favorite era, even though the overall league averages have remained about the same. Except for a few other areas we will get into tomorrow when we talk about fundamentals.

The pace of the game is more exciting today but there hasn’t been some loss of a key component we had in the 90s as part of the deal. We have about the same number of possessions and the same number of points per game both then and now. When people complain about defense, it’s just because they got duped by the 90s Knicks and Heat into thinking a clothesline is a solid defensive practice.

But to act as if the average NBA player isn’t better today is just outright foolish. It flies in the face of everything we know about progress.

If you’re mad at this and still hold the 90s as some ultimate paragon, let’s try this. If I try to argue that Bill Russell should be considered the GOAT due to his 11 rings in 13 years, the counterargument I’m sure most would make is that Russell played in the 1960s: players weren’t as good, there wasn’t as much competition.

So when it comes to Russell, we generally accept that he played in an easier league than Michael Jordan did, because the average players weren’t very good. Advances in training, nutrition, medical care, travel and other fields led to the players in the 90s generally being more advanced than those of Russell’s era.

So why do we reject the same argument when it comes to players today versus those of 30 years ago? Advances didn’t stop in 1999. And keep in mind, Jordan and Russell’s peaks were separated by about 30 years…which is about how far removed we are from when Jordan completely took over the sport.

So why can’t we accept that the string of advancements that elevate Jordan so far above Russell continued after Jordan? They certainly did but people twist that argument to make it seem like having more advancements makes the 90s greater than the 60s, while simultaneously pretending that having less advancements makes the 90s better than today.

The answer is our own stupid brains. Nostalgia doesn’t want facts it just wants to twist the narrative to fit the answer that makes us feel special.

If the 90s is your favorite decade of the NBA, there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. But be honest about it. Say it’s your favorite, even though there’s zero factual data to back it up and that’s fine by me. But don’t make up things to suit your argument that don’t hold up to five seconds of critical thinking. We have enough of that in our political debates, let’s keep it out of sports.

Join us tomorrow where I will dismantle the vague concept of fundamentals and likely make the owner of The 3 Point Conversion mad.